Retrieving a unique identifier may allow app developers, advertisers, analytic companies and others to identify the user’s device or the user himself. Furthermore, most of these identifiers are persistent means for tracking, advertising and marketing activities on devices. Unique identifiers might however be also necessary for certain app functionality to work as expected.

Appicaptor tracks app’s access to various unique identifiers that can be categorized in three different groups:

- The first group refers to mobile communication relevant IDs. Examples of this category are access to the phone’s IMEIs and MAC addresses, country code of the mobile network provider, as well as the phone / voice mail number, serial number of the SIM card and mobile subscriber ID (IMSI / TIMSI) of the user.

- The second group is identification information about the hardware or operating system given by the operating system itself. When the mobile operating system is compiled different parameters for model, hardware, serial and display size are included in the operating system build. Furthermore, a build fingerprint can distinguish different operating system builds even if the operating system version is equal.

- The third group consists of identifiers

- like the Android Device ID, Advertisement ID,

- properties that the user could configure like font size / type, audio volume, timezone, display orientation lock and screen brightness, Bluetooth pairings, power saving mode configuration, audio singnal output port (speaker, headphones, Bluetooth, etc.)

- installed app list

- hardware parameters like cpu and set of available hardware sensors (gyroscope, barometer, …)

- other parameters like battery or device memory (RAM and data) usage.

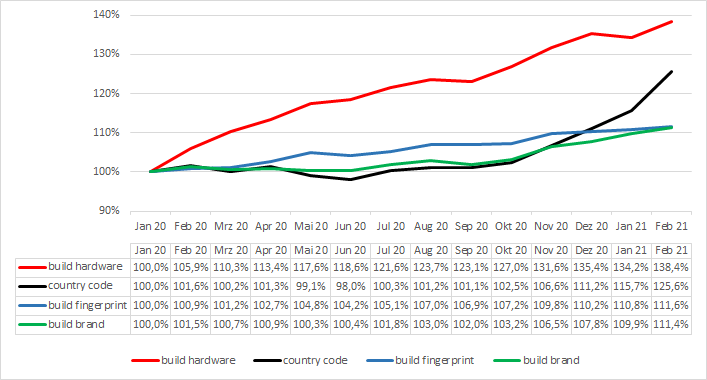

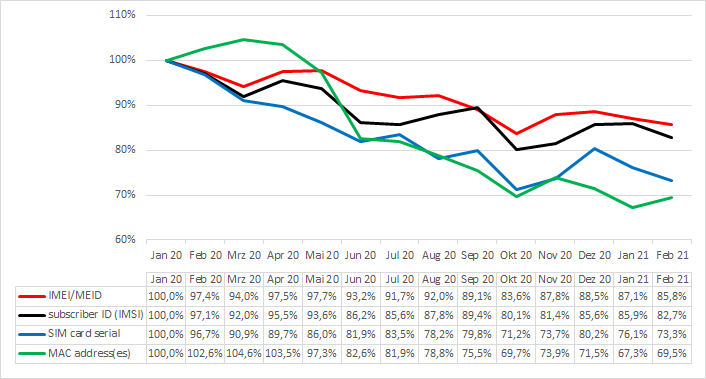

Every month Appicaptor evaluates the IT security quality of thousands of Android and iOS apps. The following two charts depict for each month which identifier usage is rising and which is falling. The charts plot the identifier usage (total number of apps within the 2,000 most popular apps in German Google Play Store that accesses an identifier) relatively to the identifier usage in January 2020.

As the relative change (given in the two charts before) does not give the perspective, which identifiers are commonly utilized and to which extent, the following table provides the absolute numbers. This table shows how many apps within the 2,000 most popular apps in German Google Play Store access an identifier in the Appicaptor analysis runs of January 2020 and February 2021. Furthermore, based on every monthly analysis run between January 2020 and February 2021 we predict a trend if the identifier usage is rising or falling based on our data.

| Name | Identifier Uage (in January 2020) | Identifier Uage (in February 2021) | Trend |

| Unique Android ID | 1,944 | 1,947 | stable |

| Build model | 1,947 | 1,945 | stable |

| Build manufacturer | 1,916 | 1,941 | ▲ |

| Build fingerprint | 1,679 | 1,873 | ▲ |

| Build product | 1,633 | 1,760 | ▲ |

| Build brand | 1,537 | 1,712 | ▲ |

| Build hardware | 1,179 | 1,632 | ▲ |

| Build display | 1,478 | 1,486 | stable |

| Country Code + Mobile Network Code | 922 | 1,158 | ▲ |

| Build serial | 877 | 1,016 | ▲ |

| Mobile Country Code | 862 | 1,000 | ▲ |

| Wifi-MAC address | 754 | 717 | ▼ |

| IMEI/MEID | 689 | 591 | ▼ |

| MAC address(es) | 547 | 380 | ▼ |

| Phone number | 281 | 264 | ▼ |

| Subscriber ID (IMSI) | 312 | 258 | ▼ |

| SIM card serial | 243 | 178 | ▼ |

| Voice mail number | 69 | 62 | stable |

The analysis of Appicaptor shows that the access to (generally speaking) unspecific unique identifiers (like the build related parameters) is currently rising. One might think that the access to unspecific unique identifiers (like the build brand or hardware) may be not an privacy issue since they are equal at thousands of devices/users. And that the access to a more specific unique identifier (like the SIM serial or phone number) should be more an privacy issue. However, there is more to take into consideration.

A detailed manual inspection of access patterns and looking on the landscape of the mobile value-chain shows that most of the accesses of unspecific unique identifiers are executed in 3rd party libraries, which are included in the app by the developer. Furthermore each of these unspecific information portions (if seen alone) can not be utilized to identify a specific device or person. But certain libraries access a magnitude of these unspecific unique identifiers, creating a device fingerprint from all them and transmit the data to a server backend. As an other example, an open source library of this type can be found here. It claimes to create a device identifier from all available Android platform signals, that is fully stateless and will remain the same after reinstalling or clearing application data.

The further manual inspection of other identified libraries shows as well, that libraries which probably execute device fingerprinting are utilized in many apps of different app types. A linkage between the device fingerprint and your person is possible, when you think of an app that utilizes an library that joins identifiers as device fingerprint and you give that app information about your person (name, email address, etc.). That would bring the provider of the library in the position to track your identity throughout the usage of different apps, based solely on unspecific unique identifiers.

So what can we learn from these numbers?

- The usage of almost all specific unique identifiers are currently falling. That trend is supposed to be related to privacy preserving functions in the mobile operating systems that limit the app’s access to correct values of these identifiers. If you enable these privacy preserving functions, fake random values are provided.

- The usage of unspecific unique identifiers is currently rising throughout all identifiers. From our perspective that rising is based on the reasoning outlined above (device fingerprinting) as well as to facilitate user identification in the presence of the current drawbacks (uncertainty if correct or fake specific unique identifiers are reported to the app by the operating system).

Therefore, in the app evaluation process one should take a look at the composition and magnitude of the list of accessed unique identifiers of an app: if many unspecified unique identifiers are accessed, this should draw one’s attention the same way as the access of an specified unique identifier should do.